Harmful Algal Blooms

Phytoplankton are of fundamental importance in the aquatic environment. Utilizing light, carbon dioxide, and various nutrients to photosynthetically produce biomass which provides the energy and material for the base of the food web. There are several thousands of extant algal species in the fresh and marine environment. In the marine environment alone, there are estimated 5,000 species of which 300 species are known to cause harmful algal blooms (HABs) where under certain conditions algal cells may proliferate into millions of cells per liter. Many HAB species produce toxins that can kill fish or other aquatic organisms or accumulate in fish or other organism’s tissues.

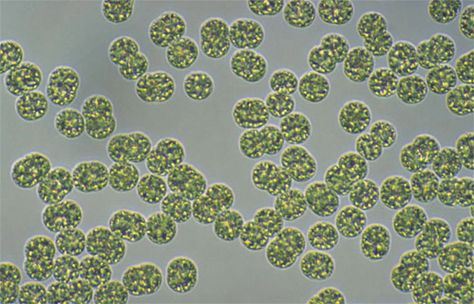

In the freshwater environment, the cyanobacteria are the most widespread and problematic algal taxa. The cyanobacteria are found in three distinct morphological groups: unicellular, either as solitary or aggregated colonies (i.e., Microcystis); differentiated filaments containing nitrogen fixing cells called heterocysts (i.e., Anabaena); and undifferentiated, nonheterocystous filaments (i.e., Oscillatoria). Nuisance and potentially toxic blooms of cyanobacteria generally occur in eutrophic or hypereutrophic waters. These blooms are influenced by pools of both nitrogen and phosphorus, coupled with the ability by many species for nitrogen fixation, blooms formation may last for prolonged periods.

In recreational waters, cyanobacteria can cause problems by decreasing dissolved oxygen concentrations during die off that may result in fish kills. In addition, cyanobacteria may produce taste and odor compounds that affect the taste of fish and can be a nuisance to those living or recreating on effected water bodies. Under favorable conditions, some cyanobacteria strains produce toxins that can cause illness and death in humans and animals. Cyanobacteria may produce one or several types of cyanotoxins that affect the liver (hepatotoxins), nervous system (neurotoxins) and skin (dermatoxins).

Cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms (cyanoHABs) are a growing concern in the global arena for their potential impact water quality, ecosystem services and human health. Increased eutrophication and climate change have resulted in the proliferation, intensification and prolonging of cyanoHABs around the world (Cook et al., 2019). Formation of blooms are regulated by water temperature, light availability and trophic conditions. Typically, cyanoHABs favor warm temperatures, high nutrient loads and low-flow conditions, conditions seen in many of the lakes and ponds of Delaware.

Blooms may vary in species composition and toxin production over time and within a water body. Cyanobacteria can also be distributed as surface scums (e.g., Microcystis), at a particular depth (e.g., Planktothrix rubescens), or throughout the entire water column (e.g., Planktothrix sp.). Distribution of cyanobacteria can be affected by winds, rainfall, and lake turnover, in addition, some species can regulate buoyancy, allowing for vertical movement in the water column. These factors are important in understanding blooms as the absence of a surface bloom is not indicative of bloom presence.

Color is also not indicative of bloom occurrence. While the name “blue-green algae” is a colloquial term for cyanobacteria, the color range of cyanobacteria can range from brown, white, black purple, red, green, or a combination. For example, Cylindrospermopsis may form blooms that are brown in color and may appear as suspended sediment. Blooms that appear green in color may be mistaken for non-harmful blooms of green algae. Proper distinguishing of cyanobacterial blooms is through processed satellite data, microscopic examination, or use of other cyanobacteria screening techniques (i.e., molecular methods, cyanotoxin field kits).

In addition to toxin production, cyanoHABs can have negative ecosystem health impacts and can raise concerns for drinking water, recreational water use and animals. While large blooms can produce excessive dissolved oxygen, when the bloom crashes it can decrease dissolved oxygen resulting in non-toxin related fish kills. Many cyanobacteria also produce taste and odor compounds that can affect the taste of fish and drinking water. Additionally, the foul smell produced by these blooms can also be a nuisance to those living and recreating on the water.

Cyanobacteria can produce a wide variety of secondary metabolites including peptides, polyketides, and alkaloids. These secondary metabolites can cause illness and potentially fatal in humans and animals, and may attack the liver, nerves, or skin. Some of the common cyanotoxins include microcystin, nodularin, saxitoxin, anatoxin-a, and cylindrospermopsin. Cyanotoxins can also bioaccumulate within the aquatic food web and may pose threat across all trophic levels. Many of the state-managed ponds have suffered from seasonal or episodic algal blooms that include potentially toxic cyanobacterial species. Microcystin has been found in low concentrations in several ponds but surveys of pond users indicated no evidence of direct toxic impacts to humans, pets, or wildlife.

Currently, there are an estimated 5000 extant species of algae in the marine environment. Among those species, approximately 300 are known to cause HABs, and like their freshwater counterpart, may produce toxins that can kill fish other marine organisms or accumulate in fish or shellfish tissue. Eutrophication of Delaware’s inland bays (DIB) has increased over the last several decades, with most of the nutrient input from agricultural and urban sources (Price, 1998; Sallade and Sims, 1997). Several harmful or potentially harmful species have been occurring frequently in DIB, with many occurring in the dead-end canals. Among those species are the dinoflagellates: Dinophysis spp., Gyrodinium instriatum, Karlodinium veneficum, and Prorocentrum minimum and several marine raphidophyte species: Heterosigma akashiwo, Chattonella subsalsa, Fibrocapsa japonica, and Viridilobus marinus.

The distribution of algae in the marine environment is influenced by a wide range of processes that include circulation, light and nutrient availability, as well as biological interactions. Algal dynamics is often driven by small to mesoscale processes where the water column is often stratified and areas where strong vertical density gradients occur, e.g., fjords, coastal lagoons, polar regions, and dead-end canals. This stratification can produce favorable conditions for the algae leading to large scale blooms, it has been observed that many large HAB species form in subsurface thin layers during bloom conditions . Algal growth has been classically measured as a whole-community response, with the use of chlorophyll as a proxy for abundance. However, this measurement has two presumptions: the community is taxonomically identical, and the community measurement adequately represents the dominant taxa. Similar to cyanoHABs, color is not indicative of a bloom occurrence. The term “red-tide” is a misnomer as color can range from green, brown, red, or “mahogany”. Proper distinguishing of blooms is through processed satellite data, microscopic examination, or use of other screening techniques (e.g., molecular methods).

In humans, toxicity can be caused by ingestion of contaminated seafood, skin contact, or inhalation of aerosolized toxins or noxious compounds. In food borne illness, HAB toxins are bioaccumulated, often without harming the vector marine organism that ingested the toxin and transfers up the food web to humans. Toxic effects are typically observed when the toxin producing species is at high concentration, however poisoning via seafood can also occur by highly toxic algae at lower concentrations. Indirect effects from toxin production have consequences on human well-being in terms of their socioeconomic impact and costs.